We’ve all heard someone say, “That’s a valid point,” or maybe, “That’s valid, but…” In everyday conversation, we tend to use “valid” to mean something sounds true or reasonable. But when it comes to logic, or philosophical notion of validity ,“validity” has a very specific meaning—and it’s a little different from just saying, “that’s a good point.”

The Structure of Validity

In logic, validity is about structure. A valid argument isn’t necessarily “true” or “good” in the everyday sense. Instead, it’s one where, if the premises are true, the conclusion must logically follow. Here’s an example:

Premise 1 (P1): All birds have feathers.

Premise 2 (P2): A penguin is a bird.

Conclusion (C): Therefore, a penguin has feathers.

In this case, if the premises are true, then the conclusion logically follows and must also be true. But saying this argument is valid isn’t the same as saying it’s “true” or a “good point” in the way we usually think. Validity here just means that the structure works: given the premises, the conclusion has to follow.

In this article, we’ll dive deeper into what makes an argument valid and how that connects to truth and soundness in logical reasoning. Let’s get into it!

Breaking Down Validity

So, let’s get into what it actually means for an argument to be “valid” in philosophy. It’s a bit more precise than how we might use it in everyday speech.

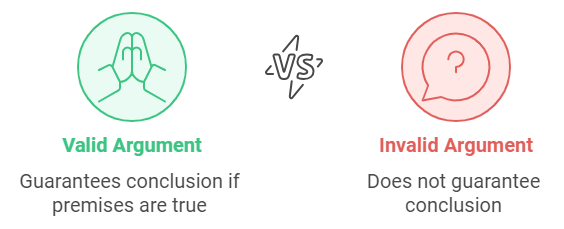

An argument is considered valid if — and only if — the truth of its premises guarantees the truth of its conclusion. So, with a valid argument, if you know the premises are true, then the conclusion has to be true as well. In this sense, validity is a kind of logical relationship between statements in an argument.

So, let’s simplify this a bit: An argument itself isn’t “true” or “false” — those terms apply to statements within it. Instead, an argument can be either valid or invalid.

Distinguishing Valid and Invalid Arguments

For a valid argument, the truth of the premises logically ensures the truth of the conclusion. We say that the premises “entail” the conclusion. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the premises or conclusion are true, only that if the premises were true, the conclusion would logically follow.

It’s impossible for a valid argument to have all true premises unless the conclusion is true-> (The premises entail the conclusion)

- Statements can be True or

False - Arguments can NOT be True or False.

- Arguments can be Valid or Invalid

If the argument is valid then the truth of the conclusion follows from the truth of its premises and vise versa.

Let’s revisit our original example about birds and feathers to understand validity better.

Premise 1 (P1): All birds have feathers.

Premise 2 (P2): A penguin is a bird.

Conclusion (C): Therefore, a penguin has feathers.

Now, is this argument valid? Yes, because if both premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. That’s the core of validity: it’s not about whether the premises or conclusion are actually true, but about the logical structure that links them.

Now, let’s see how this concept of validity holds up in a different scenario.

Exploring Validity with False Premises

To see this in another way, let’s imagine an argument with false premises but the same valid structure:

Premise 1 (P1): All fish can fly. (This is false; fish cannot fly)

Premise 2 (P2): Goldfish are fish.

Conclusion (C): Therefore, goldfish can fly.

This argument is still considered valid because, if we assume both premises are true, the conclusion would logically follow. Of course, we know the first premise is false (not all fish can fly), but the argument’s validity is about structure, not truth. If all fish could fly and Goldfish are fish, then Goldfish would logically be able to fly.

So, validity doesn’t depend on the truth of the premises; it only requires that if the premises were true, the conclusion would also follow. But what happens when we venture into invalid arguments?

Distinguishing Valid and Invalid Arguments

For a valid argument, the truth of the premises logically ensures the truth of the conclusion. We say that the premises “entail” the conclusion. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the premises or conclusion are true, only that if the premises were true, the conclusion would logically follow.

It’s impossible for a valid argument to have all true premises unless the conclusion is true; in other words, the premises entail the conclusion.

Recognizing Invalid Arguments

Note now what it means for an argument to be invalid. The truth of the argument’s premises does not entail the truth of the conclusion. For instance:

Premise 1 (P1): All cars have wheels.

Premise 2 (P2): My bicycle has wheels.

Conclusion: Therefore, my bicycle is a car.

Now, it could be the case that both premises in this argument are true, but the conclusion is false. The truth of this conclusion, in other words, does not follow from the premises, right? Just because my bicycle has wheels doesn’t mean it’s a car; bicycles and cars are two different categories of vehicles. So, this is an invalid argument.

But why does understanding validity matter, even if the truth of the premises isn’t a factor? Let’s explore this further.

The Importance of Validity

You may wonder why validity matters at all, even if the truth of the premises doesn’t matter. This is a good question to ask, and it deserves a long discussion. But the short answer is that validity is used to determine whether or not an argument obeys valid inference rules, the laws of deductive logic. That is, we are ensuring that inferences in the argument are good inferences to make.

I’ll leave you with one last example and ask you to determine its validity or invalidity:

Premise 1 (P1): All mammals are warm-blooded.

Premise 2 (P2): A goldfish is warm-blooded.

Conclusion: Therefore, a goldfish is a mammal.

What do you think?

Now that we’ve covered validity, let’s dive into soundness, a key concept that builds on our understanding of validity.

What is Soundness?

In philosophy, soundness is a key concept used to evaluate arguments. To understand soundness, we first need to revisit validity.

An argument is considered valid if it’s impossible for all of its premises to be true while its conclusion is false. For example:

Premise 1: All cats are purple <- If True (False)

Premise 2: Everything that is purple is a person <-If True (False)

Conclusion: Therefore, all cats are people. <- Not informative

This argument is valid because if both premises were true, the conclusion would also have to be true. However, we know the premises aren’t true, which means this argument doesn’t help us learn anything real. The argument doesn’t establish the truth of its conclusion. We usually want arguments that are more just valid.

So, what exactly makes an argument sound? Let’s break down the criteria.

Criteria for Soundness

To be sound, an argument must meet two requirements:

- The argument must be valid.

- All premises must be true.

If even one premise is false, the argument is unsound. The conclusion of a sound argument can NOT be false.

Evaluating Soundness with Examples

Let’s look back at our purple cat example. It was valid, but since both premises were false, it was not sound.

Premise 1: All cats are animals.

Premise 2: Some animals are not dogs.

Conclusion: Therefore, some cats are not dogs.

In this case, both premises are true, so it meets the second requirement for soundness. However, the argument is invalid because the conclusion does not logically follow from the premises. Therefore, this is still an unsound argument.

Here’s another example:

Premise 1: All fish live in water.

Premise 2: Goldfish are fish.

Conclusion: Therefore, goldfish can swim.

This argument is valid, and both premises are true, making it a sound argument. The conclusion logically follows from the premises, so we can trust that it is true.

Why Does Soundness Matter?

Knowing that an argument is sound means we can trust its conclusion to be true. If an argument meets both requirements for soundness, it cannot have a false conclusion. This means that:

A sound argument has a valid structure. All its premises are true. When we combine these two points, we find that a sound argument guarantees the truth of its conclusion.

Let’s finish with a sound argument:

Premise 1: Whales do not have fur.

Premise 2: Whales are mammals.

Conclusion: Therefore, not all mammals have fur.

This argument is valid, and since the premises are true, this is a sound argument. The conclusion must also be true.

Retrospective Reflection

As we wrap things up, I’d love for you to think about the type of reasoning—deductive, Inductive (ampliative), or abductive—related to the arguments in my first article. In this discussion, we explored concepts like validity, truth, and soundness. Reflecting on these ideas can help us determine which type of reasoning best applies to soundness. What do you think? Which type do you believe aligns with the conclusions I reached in this article?

Like listening better? Check out the podcast version below!

Leave a comment