In the first two articles, we’ve covered the basics of critical thinking—things like what makes an argument tick, the differences between deductive, inductive, and abductive arguments, and how validity, truth, and soundness all play into evaluating ideas. Now, we’re going to dive into something that trips up a lot of arguments: fallacies.

Fallacies are basically reasoning slip-ups. Sometimes they sneak into arguments unintentionally, other times they’re used to persuade people even if the logic doesn’t fully hold up. Today, we’ll look at two main types: formal and informal fallacies. We’ll go through some common examples—like equivocation and the composition/division fallacies—to see how these errors work and why they can make an argument less reliable.

By getting familiar with fallacies, you’ll start spotting weak points in arguments—whether they’re in a debate, in the media, or even in your own reasoning. Understanding fallacies isn’t just for philosophers; it’s a crucial skill for navigating everyday conversations, debates, and media

Let’s dig in and get a handle on what makes these faulty arguments tick.

Formal vs. Informal Fallacies

Let’s explore these fallacies further by categorizing them into two main types:-

- Formal Fallacies are flaws in the structure or form of an argument. If the structure is incorrect, the argument fails, even if all the premises are true.

- Informal Fallacies are issues with the content of an argument, often relying on misleading language or assumptions that don’t hold up.

Understanding these distinctions will help us see how different types of fallacies affect the overall strength of an argument.

Formal Fallacy

A defect in the form of an argument.

Structure:

P1: If x, then Y P2: Y

C: Therefore, X ->Poor form of argument

Example:

T-> P1: If someone is allergic to peanuts, then they don’t eat peanut butter.

T-> P2: Jane doesn’t eat peanut butter.

F-> C: Therefore, Jane is allergic to peanuts. (Incorrect, affirming the consequent). This poor form of reasoning can lead us to false conclusions because it ignores the possibility that there could be other reasons why Jane doesn’t eat peanut butter.

Informal Fallacy

A defect in the content of the argument.

Structure:

P1: All X are Y P2: What is X cannot be Z

C: Therefore, no X are Z

Example:

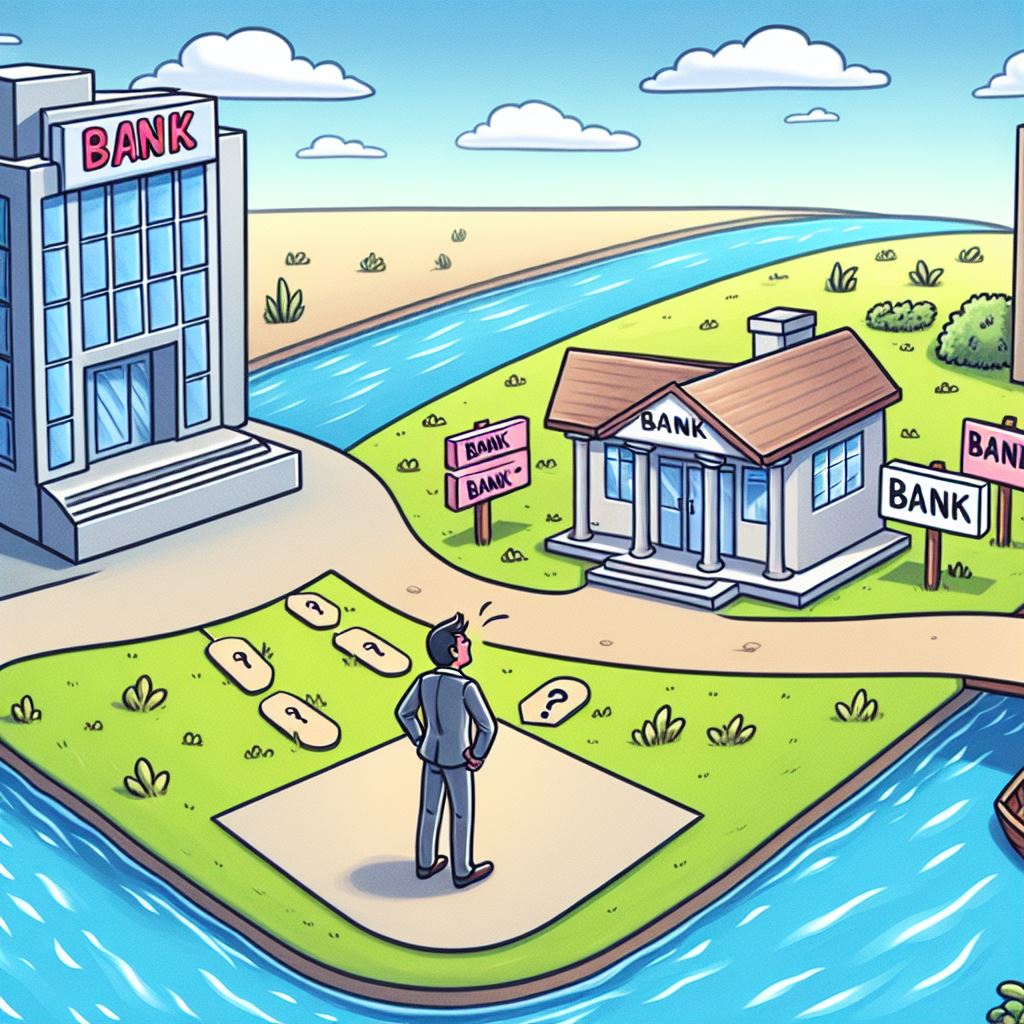

P1: The bank can refuse to lend you money.<-a financial institution.

P2: The river bank was flooded.<-the land alongside a river

C: Therefore, the river bank refused to lend me money.

This conclusion mistakenly combines the two meanings of “bank,” implying that the river bank (the land) has the ability to refuse lending money, which is nonsensical.

Another example:

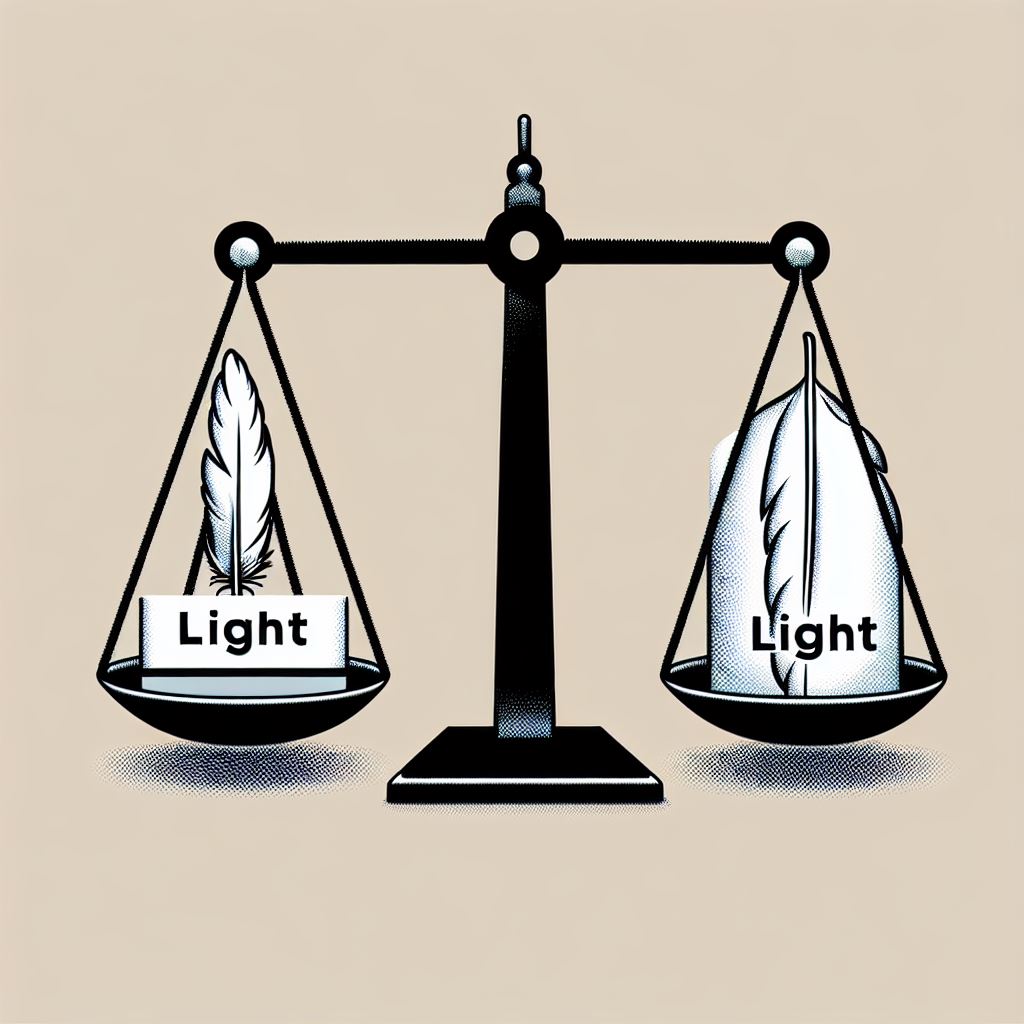

P1: A feather is light <-Wight

P2: What is light cannot be dark <-Color

C: Therefore, a feather cannot be dark. <-Informal fallacy

(Incorrect, equivocation on the word “light”).

This is equivocation, using “light” to mean two different things.

Common Types of Informal Fallacies

Let’s move on to some common informal fallacies that often slip into arguments.

Equivocation Fallacy

Example:

P1: All stars are exploding balls of gas.

P2: Miley Cyrus is a star.

C: Miley Cyrus is exploding balls of gas.

Flaw: The logic is flawed. The argument is committing a fallacy.

How to spot it: Clarify each meaning of the ambiguous term and see if the argument still holds.

If you suspect an argument is guilty of equivocation:

- Distinguish the potential meanings of the ambiguous term in an argument.

- Restate the argument without the ambiguous term so that the premises are still true.

- Evaluate: Is the translated argument valid?

- If not, the argument has committed the fallacy of equivocation.

Equivocation often leads to confusion, as it relies on ambiguous language that misleads the audience.

Fallacy of Composition

Happens when we assume that the whole has the same qualities as its parts.

Example:

P1: Atoms are colorless.

P2: Cats are made of atoms.

C: Therefore, cats are colorless. (Incorrect)

Flaw: Just because each part has a trait doesn’t mean the whole does.

Fallacy of Division

A defect in reasoning that arises when we assume that parts of some whole have the same properties as the whole they make up (converse of the fallacy of composition).

Structure:

P1: Whole A has properties a, b, and c. P2: P is a part of A.

C: Therefore, P has properties a, b, and c.

The parts may lack the properties that the whole has.

Example:

P1: My car is red, and it goes really fast.

P2: The muffler is a part of my car.

C: Therefore, my muffler is red, and it goes really fast. (Incorrect)

Flaw: Parts don’t necessarily share all properties of the whole.

Another example:

P1: The house is pink.

P2: The front door is part of the house.

C: Therefore, the door is pink. (Incorrect)

Understanding the fallacy of division is important, especially in discussions about groups or categories, as it helps prevent misunderstandings based on characteristics that may not apply to individuals.

Key Takeaway

Recognizing these fallacies helps you critically evaluate arguments by spotting weaknesses and checking if reasoning holds up logically. Fallacious reasoning doesn’t always mean a conclusion is false, but it does weaken the argument’s reliability. The next time you engage in a discussion or debate, keep an eye out for these common fallacies. By doing so, you can sharpen your reasoning and contribute to clearer, more productive conversations.

Like listening better? Check out the podcast version below!

Leave a comment