Ever been in a conversation where someone jumps to conclusions or makes a wild claim, and you’re left thinking, “Wait, how did we get here?”

It’s surprisingly easy to fall into the trap of faulty reasoning without even realizing it. That’s where logical fallacies come in—they’re like those hidden potholes in an argument that make it shaky or downright misleading.

In our previous articles, we explored several common fallacies. We looked at formal and informal fallacies, where the structure or content of an argument is flawed. We also tackled the equivocation fallacy, where ambiguous language leads to confusion, and examined the fallacy of composition and division, which involve making incorrect assumptions about parts and wholes. Most recently, we dived deep into ad hominem fallacies, where the focus shifts from the argument itself to attacking the person making the claim.

In this article, we’ll continue our journey, diving into more fallacies that often sneak into everyday conversations and debates. From the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy, which confuses correlation with causation, to the red herring that derails discussions, understanding these will sharpen your critical thinking and help you spot when an argument doesn’t quite hold up. So, buckle up and get ready for a crash course in unraveling flawed logic and keeping your reasoning on point!

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc Fallacy

The post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy, which is Latin for “after this, therefore because of this,” happens when someone assumes that just because one event followed another, the first event must have caused the second. It’s a common mistake where people mix up correlation with causation.

Structure:

(P): X happened after Y.

(C): Therefore, Y caused X.

Example:

(P): My bike broke after Alex rode it.

(C):Therefore, Alex caused it to break.

But this conclusion is jumping the gun without real proof.

(P1): My bike broke after Alex rode it.

(P2): Usually, the person who rides the bike right before it breaks is the one who caused the damage.

(C): Therefore, Alex caused it to break. (Inductive reasoning)

But jumping to conclusions based only on these premises can be misleading—it’s the classic post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy.

Adding More Evidence: Now, suppose my other roommate, Alea, saw Alex hitting the bike chain with a hammer and then told me about it. That’s much stronger evidence and makes it reasonable to conclude that Alex broke my bike.

However, it’s also possible that the bike broke due to natural wear and tear, so more context is key to avoiding assumptions.

This improved reasoning avoids the fallacy by considering additional evidence before concluding causation.

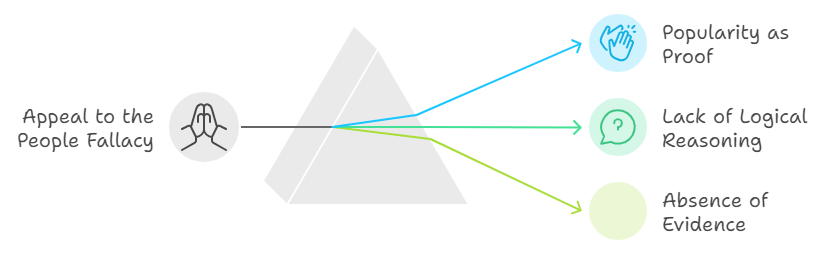

Appeal to the People Fallacy

The appeal to the people fallacy, also known as the Appeal to Popularity or argumentum ad populum, happens when someone argues that a claim is true or correct just because many people believe it. This fallacy relies on the popularity of a belief or practice as proof of its validity instead of using logical reasoning or actual evidence.

Key Point: Just because a lot of people think something is true doesn’t make it true.

Example:

(P): Millions of people think Justin Bieber has musical talent.

(C): Therefore, Justin Bieber has musical talent.

While popular opinions shouldn’t be ignored entirely, it’s essential to dig deeper and evaluate the real evidence supporting a claim, not just rely on how widely it’s accepted. Popularity alone doesn’t prove the truth.

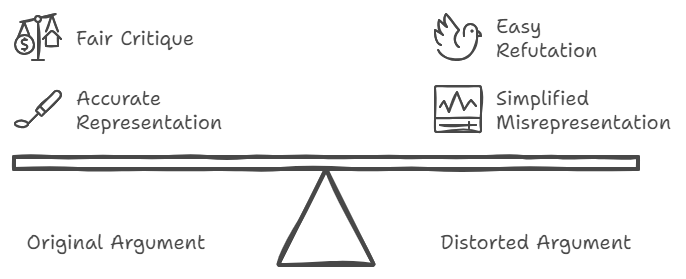

The Straw Man Fallacy

The straw man fallacy happens when someone misrepresents or distorts an opponent’s argument to make it easier to attack or refute. Instead of addressing the real argument, the person creates a weaker, exaggerated, or overly simplified version (a “straw man”) and then dismantles that version.

How it Works:

Person 1 presents position X.

Person 2 distorts position X to create position Y.

Person 2 attacks position Y.

Person 2 concludes that position X is false.

Example 1:

(P1): Advertisements for beer encourage underage drinking.

(P2): Underage drinking often has negative consequences.

(C): Therefore, advertisements for beer should be banned from TV.

An opponent might misrepresent this by saying: “You think all ads should be banned because they lead to underage drinking,” which oversimplifies the original argument to make it easier to refute.

Example 2:

(P1): The theory of evolution suggests that humans evolved from common ancestors with apes.

(P2) (Distorted): The theory of evolution says humans are no different from apes.

(C): Humans are obviously smarter than apes, so the theory of evolution is false.

This straw man ignores the actual claims of evolution and instead sets up a simplified argument that’s easy to tear down.

The straw man fallacy is especially common in political debates, where it’s used to sidestep difficult topics or discredit an opponent’s position by misrepresenting it. This tactic distracts from genuine discussion and leads to misleading conclusions.

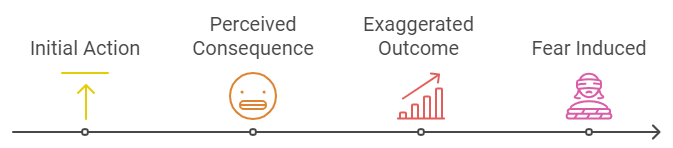

The Slippery Slope Fallacy

The slippery slope fallacy occurs when someone argues that a relatively small first step will inevitably lead to a chain of related events, culminating in a significant and usually negative outcome. This argument often exaggerates the consequences of an action to create fear or alarm about taking the initial step.

How it Works:

- A small initial action is presented as leading to an extreme series of consequences.

- The logic jumps from one step to another without sufficient evidence for the connections between them.

Example 1:

(P1): If you give Dan gum, then everyone else will see.

(P2):If everyone sees, they will ask for gum.

(P3): If everyone asks, you’ll have to give the entire class gum.

(C): Therefore, if you give Dan gum, you will have to give the entire class gum.

Example 2:

“If we allow students to redo assignments, soon they will expect to redo everything, and eventually, grades will become meaningless.”

In both cases, the fallacy lies in assuming that one event will inevitably trigger a chain reaction without any real evidence to back up the claim. This type of argument is designed to provoke fear and discourage taking the initial step.

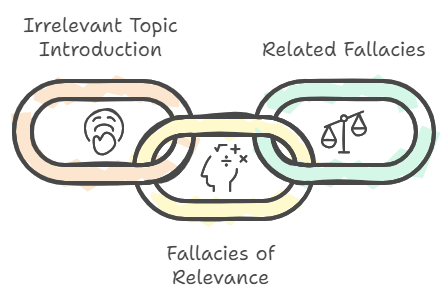

The Red Herring Fallacy

The red herring fallacy occurs when an irrelevant topic or piece of information is introduced into an argument to distract from the main issue. This tactic diverts attention away from the original point, making it harder to reach a logical conclusion based on the initial argument.

Key Characteristics:

- It shifts the focus of the discussion to something unrelated.

- It falls under fallacies of relevance, where a premise (even if true) is not directly related to the conclusion.

Related Fallacies:

- Appeal to authority: Using authority as evidence when it’s not relevant.

- Ad hominem: Attacking the person instead of addressing the argument.

Example: Imagine a debate about increasing funding for public schools. Someone might say, “But what about the rising cost of college tuition?” While college costs are important, bringing them up in this context distracts from the main issue of funding public schools.

Red herrings are often used intentionally in politics to divert attention from difficult or controversial topics by shifting the focus to a more agreeable or less contentious issue. This tactic helps avoid addressing the main argument directly.

Like listening better? Check out the podcast version below!

Leave a comment